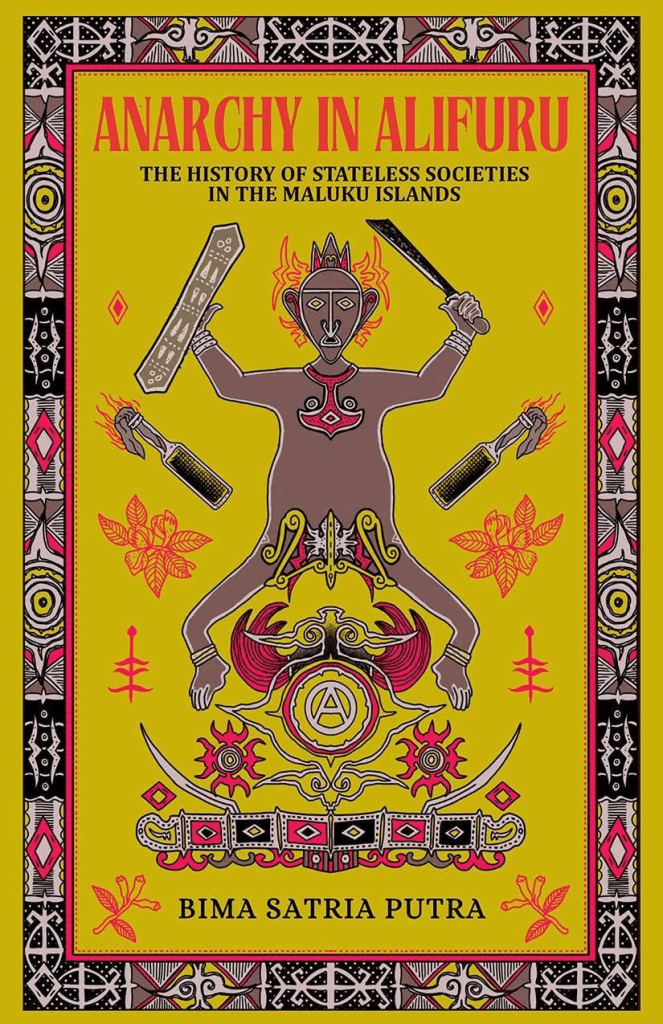

anarchy in alifuru

Anarchy in Alifuru – The History of Stateless Societies in the Maluku Islands (2025) by bima satria putra

notes/quotes via 84 pg kindle version from anarchist library [https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/bima-satria-putra-anarchy-in-alifuru]:

14

intro

15

Therefore, this book provides space for a type of historiography for those who were conquered, marginalized, and on the periphery. I attempt to reconstruct what James C. Scott, in his book The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (2009), describes it as a “non-state space.” Scott’s study focuses on the highlands of Zomia in Southeast Asia, where societies had fled from state projects – slavery, conscription, taxes, forced labor, epidemics, and warfare – of the surrounding nation-states. This book is highly provocative and has sparked ongoing academic debates about the type of “anarchist” societies that are believed to have deliberately chosen to remain stateless.

james c scott.. art of not being governed..

16

In its historical definition, anarchism is certainly stateless, but stateless societies are not necessarily anarchist. Modern anarchism, which developed in Europe, is better understood in terms of specific ideological pillars and principles. When I use the term “anarchy” here, it refers more to a broader libertarian universe, which is not always connected with historical terms but includes struggles and initiatives against authoritarianism, opposition to domination, and advocacy for egalitarian forms of relationships. Anarchy in this context has nothing to do with the revolutionary socialist tradition of anarchism as seen in Bakunin, primarily because its focus is on alternative political institutions (which are stateless) and does not address other aspects such as economic structure or gender studies. However, I am not the first to use an anarchist approach outside its historical tradition. Scott is one such example, as well as the anarchist and anthropologist David Graeber, and Pierre Clastres with his classic work on South American Indian communities – specifically the Guayaki – titled Society Against the State (1977). A global overview of this approach is provided by Harold Barclay in People without Government (1992), with the subtitle “The Anthropology of Anarchism.”

mikhail bakunin.. david graeber..

This book is essentially a “history of anarchism,” examining stateless spaces in Maluku, or the extended eastern Indonesian region, where societies continued to follow local political traditions and norms.

rather.. a history of your defn of anarchism.. all still w/in the broad spectrum of sea world

Nevertheless, I propose that this stateless space be referred to as the “Alifuru World” as a counter-narrative to the “Maluku World” proposed by Leonard Y. Andaya. From the center of Ternate-Tidore civilization [Maluku], the islands to the south were considered the domain of wild, primitive, and uncivilized people. In local terms, Alifuru, which according to van Baarda (1895) comes from the Tidore vocabulary halefuru, consists of hale meaning “land” and furu meaning “wild” or “savage.” This is also why the southernmost sea in Maluku is called the Arafura Sea.

17

Therefore, this book adopts the understanding that there are dualism of worlds, or spaces, namely the world of Maluku and the world of Alifuru. These two spaces, the state and the stateless, the center and the periphery, have dynamic, layered, and diverse relationships that vary over time.

20

Chapter 1. Non-state Spaces: The Earliest European Reports

24

Unlike Ternate-Tidore, the absence of a king or single ruler in Banda compelled these leaders to act together to enforce political control or achieve shared economic benefits based on consensuses that was achieved through deliberations.

aka: form of m\a\p.. so .. cancerous distraction

25

“they could not really be regarded as having rulers,”” according to Dutch reports, because their leaders “had very little influence over their subjects, whose opinions they had to respect, and accommodate their administration to them.

but they did have influence.. ie: consensus ness is influence.. any form of democratic admin.. any form of m\a\p

28

Each village on Kisar Island was led by orang kaya from the marna class. English navigator George Windsor Earl (1841112) observed that the orang kaya in Kisar administered justice “like a father managing his family.” When Dutch sailor Dirk Hendrik Kolff anchored in Kisar in 1825, nearly all the orang kaya on the island gathered and deliberated:

still a form of m\a\p.. ie: father rules ness.. et al.. oi

29

The debates are occasionally continued for two or three days, but they are usually settled without much difference of opinion.”

aka: cancerous distractions.. any is too much.. any is maté trump law.. any is voluntary compliance.. et al

public consensus always oppresses someone(s)

The inhabitants of Kei Islands live in villages (ohoi) led by the orang kaya, most of whom are from the mel-mel class. According to Catholic missionary Geurtjens, who worked in the early 20th century, the orang kaya in Kei “used to be very independent governors in their villages.” Van Wouden (1968: 36) commented on this:

“…we must most likely interpret this to mean that each village was essentially an independent unit… He [orang kaya] was not allowed to act arbitrarily, and for all important matters, he had to hold meetings with the ‘elders’ of the family group.”

Stratification in Kei seems to have spread to the Tanimbar Islands, as their social classification is identical. However, the life of the Tanimbar people remained democratic. In the mid19th century, a pair of Scottish explorers, the Forbes, lived for some time with the Tanimbar people. Naturalist Anna Forbes (1887: 180) reported: “they are without rules, without masters, they do not understand how to obey; you can request, pay, barter, but you cannot command.” Her partner, Henry Ogg Forbes, a botanist, also observed:

not deep enough.. need all ness.. so need sans any form of m\a\p ness.. if any form of m\a\p (ie: any form of democratic admin).. then rulers ness..et al

30

Everyone is free to express their opinions in the assembly, including women.

that’s seat at the table ness.. not legit free ness.. oi

how we gather in a space is huge.. need to try spaces of permission where people have nothing to prove to facil curiosity over decision making.. because the finite set of choices of decision making is unmooring us.. keeping us from us..

ie: imagine if we listen to the itch-in-8b-souls 1st thing everyday & use that data to connect us (tech as it could be.. ai as augmenting interconnectedness)

the thing we’ve not yet tried/seen: the unconditional part of left to own devices ness

[‘in an undisturbed ecosystem ..the individual left to its own devices.. serves the whole’ –dana meadows]

there’s a legit use of tech (nonjudgmental exponential labeling) to facil the seeming chaos of a global detox leap/dance.. for (blank)’s sake..

ie: whatever for a year.. a legit sabbatical ish transition

32

“Because of egalitarian values in Buru culture, leaders must operate not by ordering people about, but by their personal charisma and ability to persuade their kinsmen to go along with what they suggest. Whether or not people caan (literally “listen to,” and in an extended sense “follow/go along with/obey”) a leader depends on his ability to persuade them to do so. Decision making is accomplished not by declaration of the geba emngaa – either individually or collectively – but by persuasion and ultimately by consensus among all those involved in a matter.”

ordering people about and persuade ness .. same song.. forms of people telling other people what to do

40

All decisions related to public affairs were always made through deliberations involving many people. In short, there was no centralization of power and accumulation of wealth as in state societies (we will discuss this further). This is what we mean by anarchy.

if decision ness.. deliberation ness.. et al.. then centralization et al.. so to me.. not legit free.. not legit w/o rule

42

Chapter 2. State Formation in Maluku

50

The authority of Ternate and Tidore in Halmahera, Seram, and Papua, at least, were not always able to reach inland areas inhabited by the Alifuru. They merely conquered, gain recognition or respect, and this at times were facilitated by the presence of Muslim trading villages along the coast.

60

Chapter 3. The Mardika Strategy: Preventing State Formation

Siwa-Lima as Primitive War

Reports from the Europeans, whether explorers, colonial officials, missionaries, or anthropologists, were filled with prejudices inherited from the ancient Greek and Roman paradigm regarding the division between the center of civilization and the periphery inhabited by barbarians. This paradigm did not change much until early modern writers like Thomas Hobbes, in his work Leviathan (1651). According to him, the natural state of humans is a condition of anarchic war of all against all. Thus, Antonio Galvão wrote the ancient tale of Bacan in the mid-16th century:

“Once long ago there were no kings and the people lived in kinship groups (Port., parentela) governed by elders. Since “no one was better than the other,” dissension and wars arose, alliances made and broken, and people killed or captured and ransomed.”

if legit free.. dissension/wars.. et al would be irrelevant s.. this is actually ie of myth of tragedy and lord et al

The absence of kings and states is at best seen as low culture, or at worst, depicted as uncivilized. Being stateless was considered equivalent to animals, for a society without a state was perceived as no society at all. The existence of state was seen as a pillar of order and peace; anarchy meant chaos and war. Although European reports were often exaggerated, there was some truth in this matter.

oi

61

In the Archeology of Violence essay, Pierre Clastres rejects Hobbes’s understanding that primitive society is a war of all against all. Clastres explains that anarchic-primitive society cannot wage war to conquer because if that were the case, there would be winners and those who are conquered. According to him (2010265), a war of all against all would lead to the establishment of domination and power that can be forcibly exerted by the winners over the conquered. A new social configuration would then emerge, creating command obedience relationships and the political division of society into Masters and Slaves: “It would be the death of primitive society,” because the master-slave division does not exist in primitive society. In his 1838 report, British navigator George Windsor Earl also commented on the extent to which “chaos” in Leti occurred due to villages remaining autonomous from one another:

“It often ends in war, but rarely accompanied by much bloodshed.” This sentence needs to be emphasized as it accurately describes traditional warfare in Maluku.

makes no diff.. same song as long as any form of m\a\p

62

A shipwrecked sailor in Timor wrote that local “wars have more in common with children’s games than real fighting.”

in sea world.. but .. to me.. not if not yet scrambled ness..

Historians generally agree that wars in Maluku became bloodier due to colonialism. According to Andaya (1993), the European model of warfare required more personnel and weaponry compared to traditional warfare, leading to more casualties and escalating blood feuds.

Besides rejecting Hobbes’ understanding, Clastres also rejected the implied exchange concept by Lévi-Strauss: that there is war, therefore no exchange; there is exchange, therefore no war. For Clastres, exchange and alliance are merely consequences of war, because if there is an enemy, there must be allies (bound by marriage). Primitive societies cannot practice universal kinship in the exchange of women (or marriage, to prevent incest) as modern societies do, due to spatial constraints where friendship does not adapt well to distance. Exchange is easily maintained with nearby neighbors who can be invited to a feast, from someone who can accept the invitation, and who can be visited. With distant groups, such relationships cannot be established. Thus, primitive societies cannot be friends with everyone or enemies with everyone.

graeber violence/quantification law et al

63

The report quoted above shows that war and the absence of state are treated as synonyms. The weakness of authority, autonomous villages, and equality among residents – namely the absence of a state in Maluku – are seen by Europeans as conditions causing war. For Hobbes, state exists to oppose war; for Clastres, it is the opposite, war exists to oppose the state.

Indigenous Confederations

When European reports state that unity can only be achieved through the state, it implies that anarchic societies are incapable of managing collective affairs on a scale beyond their residential communities (communes)..Since the emergence of modern anarchism in the mid-19th century, anarchists have consistently proposed federalism of direct democratic communes as a replacement for the state. This institution is where people make decisions about important matters concerning their lives, instead of leaving these matters to be determined by a few individuals. Although this development was not new at its time, it was first articulated by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, often referred to as the “Founding Father of Anarchism” from France. In Du Principe Fédératif (1863), Proudhon stated that “the federal system is the opposite of hierarchy or administrative and governmental centralization.”

to me.. not opp.. rather.. same song

how we gather in a space is huge.. need to try spaces of permission where people have nothing to prove to facil curiosity over decision making..

because the finite set of choices of decision making is unmooring us.. keeping us from us..

ie: imagine if we listen to the itch-in-8b-souls 1st thing everyday & use that data to connect us (tech as it could be.. ai as augmenting interconnectedness)

the thing we’ve not yet tried/seen: the unconditional part of left to own devices ness

[‘in an undisturbed ecosystem ..the individual left to its own devices.. serves the whole’ –dana meadows]

there’s a legit use of tech (nonjudgmental exponential labeling) to facil the seeming chaos of a global detox leap/dance.. for (blank)’s sake..

ie: whatever for a year.. a legit sabbatical ish transition

66

European views should be suspected as being part of an agenda to turn indigenous societies into subjects of discipline. In such cases, colonialism often found justification in the paradigm in which Europeans felt they bore the responsibility to advance indigenous societies, which were perceived as being at a lower level of civilization or entirely uncivilized. Underneath this, the primary goal was to enhance the ability to identify, monitor, measure and calculate, govern, mobilize human resources, and exploit the resources of indigenous societies. This agenda was sometimes framed as eradicating illiteracy, pacifying conflict areas, spreading Christianity, or primarily economic development, implying that indigenous peoples were too lazy or ignorant to trade.

all the forms of people telling other people what to do

70

He also roamed the interior safely. According to Wallace, since there was no government in Aru, it was not the state that kept its people from falling into “chaos”:

“Here we may behold in its simplest form the genius of Commerce at the work of Civilization. *Trade is the magic that keeps all at peace, and unites these discordant elements into a wellbehaved community. **All are traders, and all know that peace and order are essential to successful trade, and thus a public opinion is created which puts down all lawlessness.”

*rather.. marsh exchange law et al.. peace not same thing as well behaved.. oi

**again.. peace and order not compatible.. if order ness.. not lawless ness.. carhart-harris entropy law et al.. order ness as a form of people telling other people what to do

71

Pierre Clastres, by analyzing the mode of domestic production by Marshall Sahlins, cites ethnographic evidence that primitive economies were indeed less productive because work was consumer production to ensure the satisfaction of needs and not as exchange production to gain profit by commercializing surplus goods. According to him, primitive societies are societies that refuse economy (Clastres, 2010: 198). This view might further explain the myth of the lazy native; laziness is a rejection of accumulation: “…primitive man is not an entrepreneur, it is because profit does not interest him; that if he does not “optimize” his activity, as the pedants like to say, it is not because he does not know how to, but because he does not feel like it!” (Ibid, 193).

73

Ergo, with or without a state, wars could happen. With or without a state, trade could happen. With or without a state, peace could also happen. Now, the arrangement for with or without a state is an active choice. Alifuru, therefore, aligns with David Graeber’s explanation: “Anarchistic societies are no more unaware of human capacities for greed or vainglory than modern Americans are unaware of human capacities for envy, gluttony, or sloth; they would just find them equally unappealing as the basis for their civilization. In fact, they see these phenomena as moral dangers so dire they *end up organizing much of their social life around containing them.” (Graeber, 2004: 24). We call this anarchy.

*oi

74

Conclusion. Alifuru: Conquest & Liberation

76

This is the historical perspective of those who were ruled and conquered. This approach is sometimes called “people’s history,” occasionally “history from below,” and more recently, “anarchist history.”

Instead, I propose that historically there has been a separation, two spaces and worlds, namely the state space (Maluku World) and the stateless space (Alifuru World). The relationship and position of both have been thoroughly discussed previously, and many of its elements help us explain the Maluku landscape formed today.

from what i’m reading here.. same song

..being under the shadow of government for most of the time was clearly unpleasant. It meant being regulated and supervised, taxed and levied, and their labor mobilized for things that typically only benefited the ruling class.

goes for any form of m\a\p

The most accurate conclusion at present is that the Alifuru became anarchists not because they were too ignorant to form a state. The Alifuru became anarchists also not simply because they were too far from the reach of government services and power. The Alifuru were anarchists because their society was characterized by relative equality; consensus decisionmaking; and the absence of centralized political institutions. Furthermore, they continuously fought for autonomy and actively strove to prevent themselves from forming a state. This means that the Alifuru were consciously and actively anarchist. They knew what they were avoiding and what they wanted.

to me.. this defn/description of anarchism isn’t about legit freddom.. just another verse of same song

***

And now, what is the benefit of this text?

Amid the roar of mining machinery and rainforest continuously transformed for large-scale plantation openings dragging us to the brink of mass extinction and climate crisis, *we need to rethink all the assumptions of civilization and development being touted today. What is the meaning of progress in modern history? Both capitalism and communism, though differing in their approaches, utilize the same vehicle of industrialism and believe that there are historical stages leading to progress. These stages are sometimes bridged by rapid social changes, a revolution. But Walter Benjamin has an alternative suggestion: “Marx said that revolutions are the locomotive of world history. But perhaps it is quite otherwise. Perhaps revolutions are an attempt by the passengers on the train – namely, the human race – to activate the emergency brake.”

*rather.. we need to quit thinking about those things.. need first/most: means (nonjudgmental expo labeling) to undo hierarchical listening as global detox so we can org around legit needs

77

Our economic-political order has gone too far and too fast. It is a global machine driven by the law of limitless growth that drastically reduces the Earth’s capacity to support a more habitable ecosystem. This was already Wallace’s contemplation hundreds of years ago. During his time in Aru, his worldview changed drastically. He began to question why Europeanmade goods were sold cheaper in Aru than in their place of origin, even though these goods were not truly needed by the indigenous population. He realized something was wrong with the global economic order at that time.

to me.. this is not an ie of a change in worldview.. let alone a drastic one.. oi.. if still talking cost/comparison.. et al

84

About The Author

Bima Satria Putra, born in Kapuas, Central Kalimantan, on November 4, 1995. Graduated in journalism from Fiskom UKSW, former Editor-in-Chief of the Student Press Institute Lentera. Now he is a writer, researcher, and translator. Interested in the study of history, anthropology, and ecology. His works include: Perang yang Tidak Akan Kita Menangkan: Anarkisme & Sindikalisme dalam Pergerakan Kolonial hingga Revolusi Indonesia (1908-1948) (published in 2018) and Dayak Mardaheka: Sejarah Masyarakat Tanpa Negara di Pedalaman Kalimantan (published in 2021). He is currently conducting research on the Fire Tribes Project (PSA) and remains committed to writing while serving his fifteen-year prison sentence from 2021.

_____

_____

_____

- anarch\ism(73)

- accidental anarchist

- after post anarchism

- anaculture

- anarchism and christianity

- anarchism and markets

- anarchism and other essays

- anarchism & cybernetics of self-org systems

- anarchism as theory of org

- anarchism of other person

- anarchism or rev movement

- anarchism, state, and praxis of contemp antisystemics

- anarchist communism

- anarchist critique of relations of power

- anarchist library

- anarchist morality

- anarchist seeds beneath snow

- anarchists against democracy

- anarchists in rojova

- anarcho blackness

- anarcho communist planning

- anarcho transcreation

- anarchy

- anarchy after leftism

- anarchy and democracy

- anarchy in action

- anarchy in alifuru

- anarchy in manner of speaking

- anarchy of everyday life

- anarchy works

- annotated bib of anarchism

- are you an anarchist

- art of not being governed

- at the café

- bad anarchism

- between marxism and anarchism

- billionaire and anarchists

- breaking the chains

- buffy the post-anarchist vampire slayer

- christian anarchism

- colin ward and art of everyday anarchism

- constructive anarchism

- david on anarchism ness

- don’t fear invoke anarchy

- empowering anarchy

- enlightened anarchy

- errico on anarchism

- everyday anarchism

- fragments of an anarchist anthropology

- freedom and anarchy

- goal and strategy for anarchy

- graeber anarchism law

- insurgent anarchism

- inventing anarchy

- is anarchism impossible

- kevin on anarchism w/o adj

- krishnamurti for anarchy

- libertarian socialism

- means and ends

- mobilisations of philippine anarchisms

- modern science and anarchism

- new anarchists

- nika on anarchism

- on anarchism

- post anarchism: a reader

- post anarchism & radical politics today

- post scarcity anarchism

- pure freedom

- social anarchism – gustav on socialism

- sophie on anarchism

- spiritualizing anarchism

- taoism and western anarchism

- that holy anarchist

- two cheers for anarchism

_____

_____

_____

_____