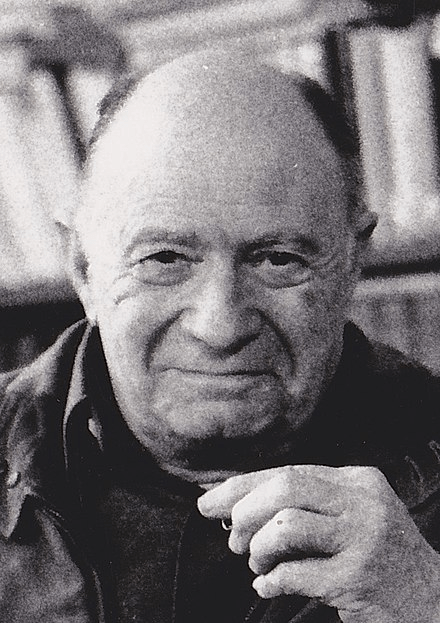

jacques ellul

adding page while reading (p 259) techno society and starting propaganda.. had already read anarchism and christianity

Jacques Ellul (/ɛˈluːl/; French: [ɛlyl]; January 6, 1912 – May 19, 1994) was a French philosopher, sociologist, lay theologian, and professor. Noted as a Christian anarchist, Ellul was a longtime Professor of History and the Sociology of Institutions on the Faculty of Law and Economic Sciences at the University of Bordeaux. A prolific writer, he authored more than 60 books and more than 600 articles over his lifetime, many of which discussed propaganda, the impact of technology on society, and the interaction between religion and politics.

anarchism and christianity (by ellul).. christian anarchism..

The dominant theme of Ellul’s work proved to be the threat to human freedom and religion created by modern technology. He did not seek to eliminate modern technology or technique but sought to change our perception of modern technology and technique to that of a tool rather than regulator of the status quo. Among his most influential books are The Technological Society and Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes.

there’s a legit use of tech (nonjudgmental exponential labeling) to facil the seeming chaos of a global detox leap/dance.. the unconditional part of left-to-own-devices ness.. for (blank)’s sake.. and we’re missing it ie: a sabbatical ish transition

Considered by many a philosopher, Ellul was trained as a sociologist, and approached the question of technology and human action from a dialectical viewpoint. His writings are frequently concerned with the emergence of a technological tyranny over humanity. As a philosopher and theologian, he further explored the religiosity of the technological society. In 2000, the International Jacques Ellul Society was founded by a group of former Ellul students. The society, which includes scholars from a variety of disciplines, is devoted to continuing Ellul’s legacy and discussing the contemporary relevance and implications of his work

By the early 1930s, Ellul’s three primary sources of inspiration were Karl Marx, Søren Kierkegaard, and Karl Barth. ..he also came across the Christian existentialism of Kierkegaard. According to Ellul, Marx and Kierkegaard were his two greatest influences, and the only two authors whose work he read in its entirety.

In 1932, after what he describes as “a very brutal and very sudden conversion”, Ellul professed himself a Christian. Ellul believes he was about 17 (1929–30) and spending the summer with some friends in Blanquefort, France. While translating Faust alone in the house, Ellul knew (without seeing or hearing anything) he was in the presence of a something so astounding, so overwhelming, which entered the very center of his being. He jumped on a bike and fled, concluding eventually that he had been in the presence of God. This experience started the conversion process which Ellul said then continued over a period of years thereafter. Although Ellul identified as a Protestant, he was critical of church authority in general because he believed the church dogmas did not place enough emphasis on the teachings of Jesus or Christian scripture.

Ellul came to like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who convinced him that the creation of new institutions from the grass roots level was the best way to create an anarchist society. He stated his view is close to that of anarcho-syndicalism, however the kind of change Ellul wanted was an evolutionary approach by means of a “… Proudhonian socialism … by transforming the press, the media, and the economic structures … by means of a federative cooperative approach” that would lead to an Anarchist society based on federation and the Mutualist economics of Proudhon. In regards to Jesus and Anarchism he believed Jesus was not merely a socialist but anarchist and that “anarchism is the fullest and most serious form of socialism”.

Ellul has been credited with coining the phrase, “Think globally, act locally.” He often said that he was born in Bordeaux by chance, but that it was by choice that he spent almost all his academic career there.

cosmo local ness.. exp\ing w/dd glocal convos

Ellul fell into a deep grief following the 16 April 1991 death of his wife, Yvette. He died three years later, on 19 May 1994 in Pessac.

Theology

While Ellul was primarily a sociologist who focused on discussions of technology, he saw his theological work as an essential aspect of his career. He began publishing theological discussions early, with such books as The Presence of the Kingdom (1948).

Much like Barth, Ellul had no use for either liberal theology (to him dominated by Enlightenment notions about the goodness of humanity and thus rendered puerile by its naïveté) or orthodox Protestantism (e.g., fundamentalism or scholastic Calvinism, both of which to him refuse to acknowledge the radical freedom of God and humanity) and maintained a roughly un-Catholic view of the Bible, theology, and the churches.

To Ellul, people use such fallen images, or powers, as a substitute for God, and are, in turn, used by them, with no possible appeal to innocence or neutrality, which, although possible theoretically, does not in fact exist. Ellul thus renovates in a non-legalistic manner the traditional Christian understanding of original sin and espouses a thoroughgoing pessimism about human capabilities, a view most sharply evidenced in his The Meaning of the City. Ellul stated that one of the problems with these “new theologies” was:

not in anarchist library

Ellul espouses views on salvation, the sovereignty of God, and ethical action that appear to take a deliberately contrarian stance toward established, “mainstream” opinion. For instance, in the book What I Believe, he declared himself to be a Christian Universalist, writing “that all people from the beginning of time are saved by God in Jesus Christ, that they have all been recipients of His grace no matter what they have done.” Ellul formulated this stance not from any liberal or humanistic sympathies, but in the main from an extremely high view of God’s transcendence, that God is totally free to do what God pleases. Any attempts to modify that freedom from merely human standards of righteousness and justice amount to sin, to putting oneself in God’s place, which is precisely what Adam and Eve sought to do in the creation myths in Genesis. This highly unusual juxtaposition of original sin and universal salvation has repelled liberal and conservative critics and commentators alike, who charge that such views amount to antinomianism, denying that God’s laws are binding upon human beings. In most of his theologically oriented writings, Ellul effectively dismisses those charges as stemming from a radical confusion between religions as human phenomena and the unique claims of the Christian faith, which are not predicated upon human achievement or moral integrity whatsoever.

In the Bible, however, we find a God who escapes us totally, whom we absolutely cannot influence, or dominate, much less punish; a God who reveals Himself when He wants to reveal Himself, a God who is very often in a place where He is not expected, a God who is truly beyond our grasp. Thus, the human religious feeling is not at all satisfied by this situation… God descends to humanity and joins us where we are.

…the presence of faith in Jesus Christ alters reality. We also believe that hope is in no way an escape into the future, but that it is an active force, now, and that love leads us to a deeper understanding of reality.

Love is probably the most realistic possible understanding of our existence. It is not an illusion. On the contrary, it is reality itself.

On technique

The Ellulian concept of technique is briefly defined within the “Notes to Reader” section of The Technological Society (1964). It is “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.” He states here as well that the term technique is not solely machines, technology, or a procedure used to attain an end.

What many consider to be Ellul’s most important work, The Technological Society (1964), was originally published in French as La Technique: L’enjeu du siècle (literally, “The Stake of the Century”). In it, Ellul set forth seven characteristics of modern technology that make efficiency a necessity: “rationality, artificiality, automatism of technical choice, self-augmentation, monism, universalism, and autonomy. The rationality of technique enforces logical and mechanical organization through division of labor, the setting of production standards, etc. And it creates an artificial system which “eliminates or subordinates the natural world.”

Regarding technology, instead of it being subservient to humanity, “human beings have to adapt to it, and accept total change.” As an example, Ellul offered the diminished value of the humanities to a technological society. As people begin to question the value of learning ancient languages and history, they question those things which, on the surface, do little to advance their financial and technical state. According to Ellul, this misplaced emphasis is one of the problems with modern education, as it produces a situation in which immense stress is placed on information in our schools. The focus in those schools is to prepare young people to enter the world of information, to be able to work with computers but knowing only their reasoning, their language, their combinations, and the connections between them. This movement is invading the whole intellectual domain and also that of conscience.

ooof.. any form of m\a\p

Ellul’s commitment to scrutinize technological development is expressed as such:

[W]hat is at issue here is evaluating the danger of what might happen to our humanity in the present half-century, and distinguishing between what we want to keep and what we are ready to lose, between what we can welcome as legitimate human development and what we should reject with our last ounce of strength as dehumanization. I cannot think that choices of this kind are unimportant.

Modern technology has become a total phenomenon for civilization, the defining force of a new social order in which efficiency is no longer an option but a necessity imposed on all human activity.

What is the solution to technique according to Ellul? The solution is to simply view technique as objects that can be useful to us and recognize it for what it is, just another thing among many others, instead of believing in technique for its own sake or that of society. If we do this we “…destroy the basis for the power technique has over humanity.”

there’s a legit use of tech (nonjudgmental exponential labeling) to facil the seeming chaos of a global detox leap/dance.. the unconditional part of left-to-own-devices ness.. for (blank)’s sake.. and we’re missing it ie: a sabbatical ish transition

On anarchy and violence

anarch\ism and violence

Ellul identified himself as a Christian anarchist. Ellul explained his view in this way: “By anarchy I mean first an absolute rejection of violence.” And, “… Jesus was not only a socialist but an anarchist – and I want to stress here that I regard anarchism as the fullest and most serious form of socialism.” …Later, he would attract a following among adherents of more ethically compatible traditions such as the Anabaptists and the house church movement

Jacques Ellul discusses anarchy on a few pages in The Ethics of Freedom and in more detail within his later work, Anarchy & Christianity. Although he does admit that anarchy does not seem to be a direct expression of Christian freedom, he concludes that the absolute power he sees within the current (as of 1991) nation-state can only be responded to with an absolute negative position (i.e. anarchy). He states that his intention is not to establish an unrealistically pure anarchist society or the total destruction of the state. His initial point in Anarchy & Christianity is that he is led toward a realistic form of anarchy by his commitment to an absolute rejection of violence through the creation of alternative grassroots institutions in the manner similar to Anarcho-Syndicalism. However, Ellul does not entertain the idea that all Christians in all places and all times will refrain from violence. Rather, he insisted that violence could not be reconciled with the God of Love, and thus, true freedom. A Christian that chooses the path of violence must admit that he or she is abandoning the path of freedom and committing to the way of necessity.

oi

Ellul’s ultimate goal was to create by evolutionary means a “…Proudhonian socialism…by transforming the press, the media, and the economic structures…by means of a federative cooperative approach…” an anarchist society based on federation and the mutualist economics of Proudhon.

not deep enough.. cooperatives et al.. mutual aid ness et al

On justice

Ellul believed that social justice and true freedom were incompatible. He rejected any attempt to reconcile them. He believed that a Christian could choose to join a movement for justice, but in doing so, must admit that this fight for justice is necessarily, and at the same time, a fight against all forms of freedom. While social justice provides a guarantee against the risk of bondage, it simultaneously subjects a life to necessities.

unjustifiable strategy ness.. and need for tech w/o judgment

In Violence Ellul states his belief that only God is able to establish justice and God alone who will institute the kingdom at the end of time. He acknowledges that some have used this as an excuse to do nothing, but also points out how some death-of-God advocates use this to claim that “we ourselves must undertake to establish social justice”. ..Ellul asks how we are to define justice and claims that followers of death-of-God theology and/or philosophy clung to Matthew 25 stating that justice requires them to feed the poor. Ellul says that many European Christians rushed into socialist circles (and with this began to accept the movement’s tactics of violence, propaganda, etc.) mistakenly thinking socialism would assure justice when in fact it only pursues justice for the chosen and/or interesting poor whose condition (as a victim of capitalism or some other socialist enemy) is consistent with the socialist ideology.

… Jesus Christ has not come to establish social justice any more than he has come to establish the power of the state or the reign of money or art. Jesus Christ has come to save men, and all that matters is that men may come to know him. We are adept at finding reasons—good theological, political, or practical reasons, for camouflaging this. But the real reason is that we let ourselves be impressed and dominated by the forces of the world, by the press, by public opinion, by the political game, by appeals to justice, liberty, peace, the poverty of the third world, and the Christian civilization of the west, all of which play on our inclinations and weaknesses. Modern protestants are in the main prepared to be all things to all men, like St. Paul, but unfortunately this is not in order that they may save some but in order that they may be like all men.

Ellul states in The Subversion of Christianity that “to proclaim the class conflict and the ‘classical’ revolutionary struggle is to stop at the same point as those who defend their goods and organizations. This may be useful socially but it is not at all Christian in spite of the disconcerting efforts of theologies of revolution. Revelation demands this renunciation—the renunciation of illusions, of historic hopes, of references to our own abilities or numbers or sense of justice. We are to tell people and thus to increase their awareness (the offense of the ruling classes is that of trying to blind and deaden the awareness of those whom they dominate). Renounce everything in order to be everything. Trust in no human means, for God will provide (we cannot say where, when, or how). Have confidence in his Word and not in a rational program. Enter on a way on which you will gradually find answers but with no guaranteed substance. All this is difficult, much more so than recruiting guerillas, instigating terrorism, or stirring up the masses. And this is why the gospel is so intolerable, intolerable to myself as I speak, as I say all this to myself and others, intolerable for readers, who can only shrug their shoulders.”

If the disciples had wanted their preaching to be effective, to recruit good people, to move the crowds, to launch a movement, they would have made the message more material. They would have formulated material goals in the economic, social, and political spheres. This would have stirred people up; this would have been the easy way. To declare, however, that the kingdom is not of this world, that freedom is not achieved by revolt, that rebellion serves no purpose, that there neither is nor will be any *paradise on earth, that there is no social justice, that the only justice resides in God and comes from him, that we are not to look for responsibility and culpability in others but first in ourselves, all this is to ask for defeat, for it is to say intolerable things.

?*

On media, propaganda, and information

Ellul discusses these topics in detail in his landmark work, Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. He viewed the power of the media as another example of technology exerting control over human destiny. As a mechanism of change, the media are almost invariably manipulated by special interests, whether of the market or the state.

propaganda – any form of m\a\p

Also within Propaganda Ellul claims that “it is a fact that excessive data do not enlighten the reader or the listener; they drown him. He cannot remember them all, or coordinate them, or understand them; if he does not want to risk losing his mind, he will merely draw a general picture from them. And the more facts supplied, the more simplistic the image”. Additionally, people become “caught in a web of facts they have been given. They cannot even form a choice or a judgment in other areas or on other subjects. Thus the mechanisms of modern information induce a sort of hypnosis in the individual, who cannot get out of the field that has been laid out for him by the information”. “It is not true that he can choose freely with regard to what is presented to him as the truth. And because rational propaganda thus creates an irrational situation, it remains, above all, propaganda—that is, an inner control over the individual by a social force, which means that it deprives him of himself”.

to me .. deeper.. ie: curiosity over decision making.. finite set of choices of decision making is unmooring us.. et al

and to me.. to date.. all ‘info’ .. non legit.. ie: from whales in sea world

On humanism

In explaining the significance of freedom and the purpose for resisting the enslavement of humans via acculturation (or sociological bondage), Ellul rejects the notion that this is due to some supposed supreme importance linked to humanity. He states that modern enslavement expresses how authority, signification, and value are attached to humanity and the beliefs and institutions it creates. This leads to an exaltation of the nation or state, money, technology, art, morality, the party, etc. The work of humanity is glorified and worshiped, while simultaneously enslaving humankind.

… man himself is exalted, and paradoxical though it may seem to be, this means the crushing of man. Man’s enslavement is the reverse side of the glory, value, and importance that are ascribed to him. The more a society magnifies human greatness, the more one will see men alienated, enslaved, imprisoned, and tortured, in it. Humanism prepares the ground for the anti-human. We do not say that this is an intellectual paradox. All one need do is read history. Men have never been so oppressed as in societies which set man at the pinnacle of values and exalt his greatness or make him the measure of all things. For in such societies freedom is detached from its purpose, which is, we affirm, the glory of God.

Before God I am a human being… But I am caught in a situation from which there is truly and radically no escape, in a spider’s web I cannot break. If I am to continue to be a living human being, someone must come to free me. In other words, God is not trying to humiliate me. What is mortally affronted in this situation is not my humanity or my dignity. It is my pride, the vainglorious declaration that I can do it all myself. This we cannot accept. In our own eyes we have to declare ourselves to be righteous and free. We do not want grace. Fundamentally what we want is self-justification. There thus commences the patient work of reinterpreting revelation so as to make of it a Christianity that will glorify humanity and in which humanity will be able to take credit for its own righteousness.

_______

_______

______

_______

_____

______

_______

______